The Handbag's Tale

Medieval or modern, handbags reveal their bearers’ secrets more than they hide them. An Object Lesson.

I had started out thinking handbags and purses were the same thing.

I was a handbag newbie, an unpaid writer, an impartial observer hired as a ghost memoirist for the CEO of a luxury-handbag resale site. Having grown up in Los Angeles, I had a cursory sense of the major brands: Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Hermès—but like many of my bookish friends, I had dismissed such flashy handbags as frivolous.

Working in the startup, I was surrounded by stacks of bags, fielding questions from visitors who could not contain their awe. I became intimately acquainted with their proper names (the Kelly), their exorbitant price tags (last year, Christie’s HK sold a matte Himalayan crocodile-skin Birkin for $300,168), and the reverence they command.

I narrated the CEO’s personal story in vignettes developed around her most memorable bags. It was a tale of empowerment, a progressivist narrative from imitation to high-end. These bags were the synecdoche of the whole woman. They marked a leap in class, but also a spiritual triumph—one that mystified me. Where did the mythos of this curious handbag species begin? Where does it end?

The word “purse” comes from the Medieval Latin bursa. In the Middle Ages, these leather bags were strung around the neck or waist. They were utilitarian—and unisex. But the unisex sack of leather did not evolve into the handbag until the 19th century. And the seasonal flux of the fashion handbag didn’t arrive until even later. Even so, their purpose has remained surprisingly steadfast: to expose their wearer’s social station.

* * *

As someone who always carried a

backpack instead, I had started with the belief that there was no

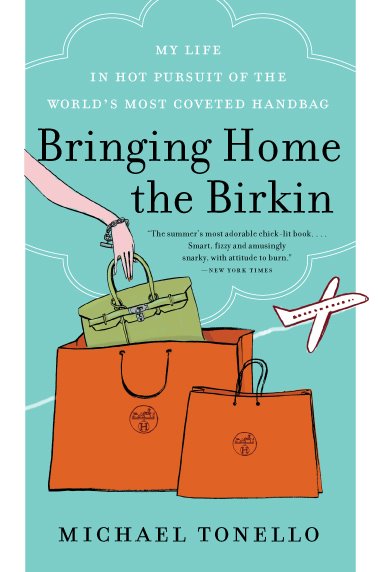

supreme purse, no one bag to rule them all. But handbag aficionados would soon inform me I was wrong. There was an end-all-be-all bag: “Haven’t you heard, darling, of the Birkin?”I knew Jane Birkin from those black-and-white boudoir pictures with Serge Gainsbourg, but what I didn’t realize was the bag made by Hermès in the chanteuse’s honor was not something one just buys. This bag was about competition. As a rule, even a wealthy woman cannot simply walk into a boutique and leave with a Birkin. First she must be placed on an indeterminable queue. The wait time is inconsistent and mysterious. Status can reduce it, as can the illusion of status. Take for example Mr. Tonello, the clever fashion buyer and Birkin reseller who would first pile up on scarves and accessories and request a Birkin at the last minute. BRIC nations can’t get their hands on enough bags, and in Hong Kong a luxury bag is valuable enough to qualify its owner for a loan on the spot.

Handbags signified a privileged status long before Jane Birkin spilled her straw bag on a flight next to Jean-Louis Dumas, the CEO of Hermès. In the late 19th century, women wore chatelaines—belts or clasps with attached chains for storing household items. They marked a woman’s domestic status, signaling who was the lady of the house and who was just a servant. Precious metal chains signified a wealthy woman, and the chatelaine with the most keys revealed who had total authority via access.

As industrialization took hold, travel picked up too. The train case emerged, a prototype for the modern handbag, and became an outward sign of mobility. Handbags also started to signify the freedom of a woman’s body. The layers of fussy underclothes and petticoats common before the late 19th century also allowed stowage of carrying bags underneath. But once women freed themselves from those garments, exposing more of their physical form, they lost the space for pockets. The external bag offered a practical solution.

And this new result of fashion emancipation—called the reticule, a small bag on a chain—could be marked as the beginning, too, of its homophone, ridicule. The external bag quickly became a constraint, a source of admonition. As Theresa Tidy, the ever-proper author of Eighteen Maxims of Neatness and Order, wrote in 1819, “Never sally forth from your own room in the morning without that old-fashioned article of dress—a pocket. Discard forever that modern invention called a ridicule (properly reticule).”

The shame of handbags is not limited to the physical object imposing space.

The example shows a turning point, when a bag began to signify not only status but also shame. Whatever men carried was tucked away out of sight in their trousers; whatever women carried was, by virtue of being exposed, flaunted.

Today still, handbags impose conflicting rules of etiquette. Even the most compact handbags seem to impose themselves in all sorts of social scenarios. A quick Google search will yield conflicting results for the etiquette, with people astounded how long they’ve been getting it wrong. What does one do while sitting on a stool if the bar doesn’t have a hook to hang it? When out to dinner is it preferable to hang your bag on the back of the chair, set it on the table, on the seat behind your back, on the lap, or on the floor to your right? Is it gauche to hand it to the person sitting next to an open seat? At dinner parties, do you hang it on a coat rack in the entryway, or house it on the bed with the coats, or keep it on your person?

* * *

The shame of handbags is not limited to the physical object imposing space. It also produces metaphysical weight.At Yes Lady Finance, the mortgage broker that writes short-term loans against Birkins, bankers lend up to half the value of the bag. The CEO, Byron Yiu, told Reuters that almost everyone who takes out a handbag loan will come back to retrieve the bag. People imbue their bags with meaning, the loss of which would be traumatic.

The same sentimentality that ensures Hong Kong ladies’ creditworthiness also underlies handbag hoarding. Women admit to the excessive number they own and their attachment to each, often for the memories they evoke. Some women I met confessed to loving some more than their own children (not to mention others’ children).

Working for the handbag start up, I learned that attachment was the greatest challenge of luxury-handbag resale. Finding Birkin owners was easy. But getting them to let go of their bags for resale was a complex endeavor involving nothing short of emotional manipulation.

I met with a handbag-inventory expert. She was a Birkin sleuth, scanning long client lists, making inquiries, calculating a client’s likely emotional resistance. She drove her Mercedes all over Southern California, hoping to bag bags in wealthy women’s homes. I wondered if women resisted her intrusion, or if they expected praise for their collections. And how did she convince women who clearly did not need the money?

During the four months I wrote the memoir, I was physically surrounded by luxury handbags. When women came to drop them off, I told them about my project and asked if they had any bag stories they wanted to share. Herschel backpack hanging from my desk chair, I was trusted as an unthreatening outsider. Without fail, the regret they had initially felt handing over their beloveds would clear in the act of sharing their stories with me.

Unlike the Birkin sleuth, I indulged their emotions. A Birkin priest hearing confessions of obsession, of greed, of guilt—especially the old relationships and bad choices that had facilitated the bag’s acquisition in the first place. Even the expensive Birkin, with its implications of wealth and therefore choice, might just as much imply imprisonment. Just as an onlooker might question a young woman coupled to an old man, a Birkin on the arm can say, “the bag chose me, not the other way around.”

Sitting with these women behind a fortress of handbags, I synthesized the obvious truth of the handbag: From chatelaine to reticule to designer bag, the handbag has always offered both freedom and yoke. It encapsulates a fact about its owner, and reveals that fact as much as, or more than, it conceals her belongings.

No comments:

Post a Comment