For two decades, Hermès has managed to make its luxury goods both impossibly exclusive and widely available, driving strong profits and growth.

PARIS, France — For

consumers and investors alike, Hermès is the quintessential luxury

brand, seen as having the most exclusive and desirable goods on the

market. But real exclusivity is not much of a business model — Leonardo

da Vinci paintings are exclusive, but trading in his artwork offers

little scope for growth or profit. And yet, among the major luxury goods

companies I monitor, including LVMH and Kering, Hermès has reported the

highest return on invested capital and the best operating profit after

tax in 13 of the past 15 years. Sure, Hermès sells exquisitely made

products, but so do many other companies. So what makes Hermès unique?

The convenient explanation is capacity constraints. Hermès frustrates demand and makes it difficult for people to buy its most coveted products. But here, too, Hermès is not alone, even if it does push things to the extreme. In today’s personal luxury goods sector, blending craftsmanship and customisation and with modern industry and technology has created the paradox of selling exclusivity by the million. And Hermès is the world champion in the art of leading people to believe its products are exclusive and unique. Indeed, Hermès has managed to appear exclusive and to maintain that appearance for years, all whilst selling a trainload of products every day with high margins.

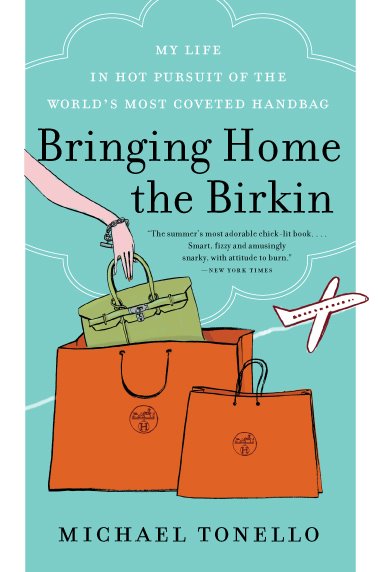

The fact that people consider the Birkin handbag to be exclusive is an astonishing feat. I calculate there must be more than a million Birkin bags in circulation. Very few handbag brands can claim such significant volume on any of their models and even fewer can claim to have a luxury product with the exclusive reputation of the Birkin.

Better still is Hermès’ skill at creating a halo of exclusivity around each product it sells, no matter how trivial: ties for €150, scarves for €350, perfume for €85, fashion bracelets for €450. Consumers can buy any of these products and leave the Hermès store feeling like a million dollars. To achieve this, Hermès has implemented one of the most effective stratagems for reconciling high sales volumes with a reputation for exclusivity: category segregation. This involves confining iconic, core category products to high-end price ranges only, while focusing other product categories with lower price points on aspirational consumers.

Other companies have tried this approach, but none come close to Hermès’ level of success. Cartier segregates its product categories when it comes to advertising, featuring only exclusive pieces of jewellery in its campaigns. Similarly, several large soft luxury brands are attempting to segregate leather handbags, but the jury is still out on whether they will stick to this strategy, given the fierce attack by accessible luxury players such as Michael Kors.

The recent launch of Apple Watch Hermès is the nth example of the luxury brand’s extraordinary ability to appear both impossibly exclusive and widely available. For Apple, the partnership rescues the “cool factor” of the Apple Watch, which was drawing perilously close to appearing geeky despite the company’s attempts to build coolness around its luxury-level gold model. For Hermès, it attracts attention back to a category with which the brand has been struggling and offers an easier entry point for aspirational consumers. It sells a little piece of the brand — a Hermès leather band — at a very significant premium and, I assume, a considerable margin.

That said, the future for the luxury market’s master of seduction looks decidedly less assured. Over the past twenty years, Hermès has achieved both high organic growth and very significant margin expansion. Going forward, neither of the two is likely to continue, as the company seems to be set on a course of mid to high single-digit organic growth and is probably close to peak margins.

The convenient explanation is capacity constraints. Hermès frustrates demand and makes it difficult for people to buy its most coveted products. But here, too, Hermès is not alone, even if it does push things to the extreme. In today’s personal luxury goods sector, blending craftsmanship and customisation and with modern industry and technology has created the paradox of selling exclusivity by the million. And Hermès is the world champion in the art of leading people to believe its products are exclusive and unique. Indeed, Hermès has managed to appear exclusive and to maintain that appearance for years, all whilst selling a trainload of products every day with high margins.

The fact that people consider the Birkin handbag to be exclusive is an astonishing feat. I calculate there must be more than a million Birkin bags in circulation. Very few handbag brands can claim such significant volume on any of their models and even fewer can claim to have a luxury product with the exclusive reputation of the Birkin.

Better still is Hermès’ skill at creating a halo of exclusivity around each product it sells, no matter how trivial: ties for €150, scarves for €350, perfume for €85, fashion bracelets for €450. Consumers can buy any of these products and leave the Hermès store feeling like a million dollars. To achieve this, Hermès has implemented one of the most effective stratagems for reconciling high sales volumes with a reputation for exclusivity: category segregation. This involves confining iconic, core category products to high-end price ranges only, while focusing other product categories with lower price points on aspirational consumers.

Other companies have tried this approach, but none come close to Hermès’ level of success. Cartier segregates its product categories when it comes to advertising, featuring only exclusive pieces of jewellery in its campaigns. Similarly, several large soft luxury brands are attempting to segregate leather handbags, but the jury is still out on whether they will stick to this strategy, given the fierce attack by accessible luxury players such as Michael Kors.

The recent launch of Apple Watch Hermès is the nth example of the luxury brand’s extraordinary ability to appear both impossibly exclusive and widely available. For Apple, the partnership rescues the “cool factor” of the Apple Watch, which was drawing perilously close to appearing geeky despite the company’s attempts to build coolness around its luxury-level gold model. For Hermès, it attracts attention back to a category with which the brand has been struggling and offers an easier entry point for aspirational consumers. It sells a little piece of the brand — a Hermès leather band — at a very significant premium and, I assume, a considerable margin.

That said, the future for the luxury market’s master of seduction looks decidedly less assured. Over the past twenty years, Hermès has achieved both high organic growth and very significant margin expansion. Going forward, neither of the two is likely to continue, as the company seems to be set on a course of mid to high single-digit organic growth and is probably close to peak margins.

No comments:

Post a Comment