Sunday Book Review

‘Primates of Park Avenue: A Memoir,’ by Wednesday Martin

A

few pages into “Primates of Park Avenue,” I raised an eyebrow as high

as a McDonald’s arch. Was Wednesday Martin, a Midwestern-born Ph.D.,

trying to explain the rites of the Upper East Side to me, an

autochthonous Manhattanite schooled at one of the neighborhood’s top

“learning huts”? She was a late transfer to the New York troop — a

particularly vicious troop, at that — and it’s a weak position to be in

throughout the primate kingdom, whether human or monkey.

I

underestimated Martin with few repercussions, but the SoulCycled,

estrogen-dimmed and ravenously hungry young mothers who similarly

exhibited New York’s inbred superciliousness have done so at their

peril, because now she’s gone and told the world their tricks. “I was

afraid to write this book,” Martin confesses, but I guess she got over

it. Instead, she obsessively deconstructs the ways of her new tribe,

from the obvious — “No one was fat. No one was ugly. No one was poor.

Everyone was drinking” — to the equally obvious but narratively rich:

“It is a game among a certain set to incite the envy of other women.”

The

result is an amusing, perceptive and, at times, thrillingly evil

takedown of upper-class culture by an outsider with a front-row seat.

The price of the ticket, a newly purchased Park Avenue condop in the 70s

with a closet designated exclusively for her handbags, wisely goes

unmentioned, the better to establish rapport with readers in Des Moines.

The

Dian Fossey-in-velvet-kitten-face-flats act is a gimmick more suited to

a midcareer Jennifer Aniston movie. But the sociology rings true, even

if the codification can be off (a common practice among stay-at-home

moms and their working husbands in a flush year called “presents under

the Christmas tree” is here designated a “wife bonus”). And Martin’s

writing is confident and evocative, if excitable. “It was the land of

gigantic, lusciously red strawberries at Dean & DeLuca and snug,

tidy Barbour jackets and precious, pristine pastries in exquisite little

pastry shops on spotless, sedate side streets,” she says of her adopted

habitat. “Everything was so honeyed and moneyed and immaculate that it

made me dizzy sometimes.”

Beyond

the private planes, waterfront in the Hamptons and apartments with

ceilings high enough to fit a bouncy castle for a child’s party, Martin

sees a strict social pecking order in which the community’s animating

energy derives mostly from children’s matriculation at a “TT” (top-tier)

school. Lululemon, the leisure wear of the lady who lunches, to Martin,

is “a kind of girdle or exoskeleton, smoothing out bumps, holding

everything up and in while they appeared to bear all.” The grueling,

high-priced barre class Physique 57 is a wonder, and she is agog at “the

indescribable strangeness of this disconnected group sex experience.”

Her reading of the fashion attire of real estate brokers for “triple

mint” apartments is brilliant.

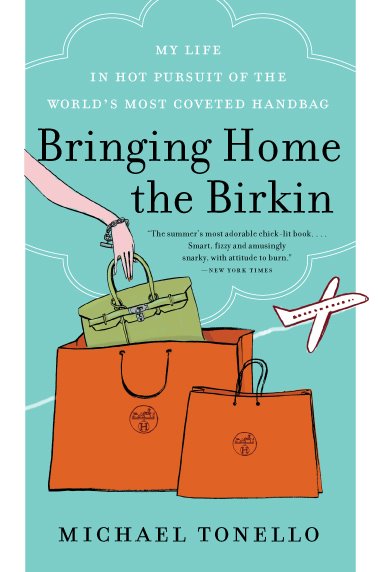

One

requires security and protection in such a world. Martin finds it in a

Birkin bag, which she absolutely must have as her “sword and shield” on

the sidewalks west of Lexington Avenue. When she whispers this desire to

her husband, “he just sort of groaned,” though he quickly agreed to buy

it the next day. “I laughed — a loud, braying, mirthless, ungenerous

laugh that seemed to alarm him,” she writes. How could he be so jejune

to think that Hermès lets you waltz in and buy a Birkin? According to

the BBC, “demand is such that there is no longer a waiting list for the

bag, in the classic sense of the term. It’s a wish list, not an order

list.” The scarcity of the Birkin, as Martin points out, is the

thing-in-itself for upper-class women, a way to “rejuvenate our own

scarcity, to reinvigorate the sense of everyone in our society of our

own value.”

You

need a taste for these kinds of insights to make it through Martin’s

book, and she’s less successful at tying up loose ends by sharing a

harrowing experience of fertility. Try as she might to convince us that

it was only in her darkest period that she realized the power of the

Upper East Side community, she doesn’t quite cleanse the palate of the

tart taste of her prior chapters. But at a time when a social comedy of

the rich à la Tom Wolfe has been lost in national discourse — the

hard-news press, at the moment, likes billionaires as reprehensible,

emotionally stunted villains, and soft news is so deeply in thrall to

luxury advertising revenue that it can’t afford anything but fawning

coverage — it’s fun to dip into a sophisticated, if silly, look at the

Upper East Side’s Twilight Zone. “Primates of Park Avenue” is also a

good reminder that as much as we may envy the wealthy, they fight every

day for a place in their own social hierarchy, too.

PRIMATES OF PARK AVENUE

A Memoir

By Wednesday Martin

248 pp. Simon & Schuster. $26.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/31/books/review/primates-of-park-avenue-a-memoir-by-wednesday-martin.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/31/books/review/primates-of-park-avenue-a-memoir-by-wednesday-martin.html