New Chief of Design House Says Family Will Fight to Remain Independent

By

Christina Passariello/Wall Street Journal

PARIS—The founding family has taken the

reins again at Hermès, battening down the hatches after facing an

incursion from a rival. Last month,

Axel Dumas,

a 43-year-old former banker, took over as chief executive of the

French luxury-goods house, succeeding

Patrick Thomas,

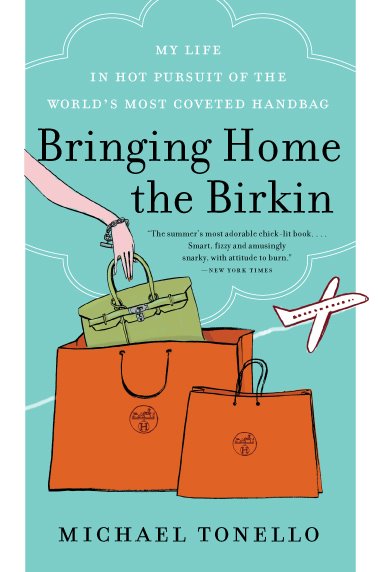

the only outsider to ever run the company, famous for its Kelly

bags and silk scarves.

Mr. Dumas and his cousins, members of the sixth generation, have stepped into the breach in response to

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton

MC.FR +1.22%

building up a 23% stake. The family pooled 50% of the company's

capital in a trust to keep it out of the hands of the luxury juggernaut.

But LVMH hasn't signaled any intention of backing down.

It

is easy to understand why Hermès would be appetizing prey. The company

is positioned at the top end of the luxury-goods category and has proven

immune to the slowdown in China that is affecting many of its

competitors. Hermès' biggest conundrum is how to keep up with demand.

In

an interview from his eighth-floor office with a view onto Montmartre,

Mr. Dumas sat down with The Wall Street Journal to discuss family unity,

how he deals with the unwanted shareholder and why price isn't an

indicator of exclusivity. Excerpts:

WSJ: What does it change for Hermès to go back to being run by a family member?

Mr. Dumas: I'm

the seventh CEO of Hermès, and part of the sixth generation [of the

family]. When the board selected me, there was more of a discussion of

an outsider or an insider rather than a family member or not. Eventually

they decided on an insider who happens to be a family member.

WSJ: How did the family select you to run the company?

Mr. Dumas: We

let our board members who are not part of the family select from the

top 10 or 20 managers. If you try to organize a beauty contest between

members of the family, it is a recipe for resentment a few years after.

One thing which is always important

in a family business is how you arrive at a decision. When you have a

very small number of family members, it is easy to be in unanimity. When

you are a very large family, more than 200, it is always the majority,

you just vote on it. In my generation, there are over 40 members. So

it's a mix of the two. We still long for unanimity.

WSJ: How does your family maintain its traditions?

Mr. Dumas: We've

been raised together. With all my first cousins, we shared the same

country house (in Normandy). But there was no specific time where we all

would come together and wear nametags.

There's

been a trend in Europe of consolidation, not only in luxury, where a

family company, because of a question of size, is absorbed in a larger

conglomerate. It is very important that the family is never complacent

and keeps its entrepreneurial spirit.

WSJ: Was LVMH's entry into your capital due to the family being complacent?

Mr. Dumas: It

surprised everyone. We are fighting to keep Hermès independent. It will

be the fight of our generation. We are a company with 177 years of

history. So we've seen struggle from time to time. We invested all our

money in 1928 to open a store in New York, just before the Great

Depression. It was 10 years of trauma for the family thanks to that.

WSJ: Now that you are the public face of the family, what kind of relationship will you have with LVMH?

Mr. Dumas: As a CEO, my role is to grow the company as much as possible, taking into account the global interest of all the shareholders.

WSJ: Including LVMH.

Mr. Dumas: The best benefit they can have is by realizing the capital gain on their shares.

WSJ: So you are encouraging them to sell?

Mr. Dumas: It would create great results that will increase their profit.

WSJ: Your sales have tripled in the past 10 years. Where will Hermès be 10 years from now?

Mr. Dumas: It

is not about a set of figures by itself. It is about the growth of all

our métiers [product lines]. We are going to continue to invest in our

production facilities. We want to have Hermès be even more diverse and

balanced. Likewise in our geographical expansion. In the 19th century,

we were centered around the Atlantic Ocean. Probably in 20 years we will

be centered around the Pacific Ocean. From the West Coast of the U.S.

to China to Southeast Asia.

WSJ: There is a paradox in luxury, of selling lots of goods that have an aura of exclusivity. How do you manage this paradox?

Mr. Dumas:

When we have had discussions about changing the way we do things to

produce more, we always say no, to stay authentic. My great-grandfather

Emile Hermès

was sent to the U.S. during the First World War to buy some

leather for the French cavalry and to look at Fordism—assembly line

production. He was very impressed. He came back to Hermès and wrote a

memo: "Never for us."

WSJ: Every

year you are able to make more bags because you increase your

production facilities. Even at your high price point, are you not

concerned about the ubiquity of your bags?

Mr. Dumas: I

don't think the price point is the relevant measure of our exclusivity.

I am a little bit always taken aback when I hear, "We want to be more

exclusive so we're going to sell more expensive bags." I think that the

volumes that we have are still quite insignificant compared with the

rest of the market.

WSJ: Your prices have risen much faster than inflation. To what extent are consumers beginning to resist these price increases?

Mr. Dumas: I

think we are very reasonable because there is no price marketing at

all. It is just due to wage increases in France and the cost of the

material. The price of good cashmere has increased 20%. The divide is

not based on price, it's based on what you get for the product. That's

why you see that the high-end luxury market did well. The lower end of

the market is doing well also. Because for the two of them you get what

you pay for. The middle—when the construction is closer to the lower end

but you sell it at a price closer to high end—suffers the most in our

industry.

WSJ: You

said that your prices are determined by costs. At the same time, you

recently announced a record high operating margin. How do you justify

that?

Mr. Dumas: It's

our operating margin. I won't say we've seen a great change in our gross

margin. In each métier, we try to have them the same profitability, so

we can have a huge spike in one and a decrease in the other and it won't

have a major impact on the operating margin.

WSJ: The crackdown on gifting in China has affected luxury-goods growth. How long do you think it will last?

Mr. Dumas:

When the big anticorruption wave ends, the attitude toward consumption

will be easier. We are less affected because we're very specific about

what kinds of credit cards we take. When you're buying for yourself,

usually you pay with your own credit card and not a gift card that has

been given by someone else.

WSJ: How is Hermès affected by the slow economic growth in France?

Mr. Dumas:

Our sales in December were telling of the evolution. We had more

customers than before, but the average basket was lower. We see that

consumers were quite cautious about the economic perspective. The main

issue in France globally is our unemployment, which is at an

unsatisfactory level. Sometimes we are very good in productivity, but it

doesn't help employment.

WSJ: Your ancestors often ran Hermès until they were 80 years old. Is this a lifelong commitment for you?

Mr. Dumas:

As long as the family will be happy, and as long as I believe I can

serve Hermès in a good way, I will be delighted. I think it's the best

job in the world.